Ping Zheng—aka Zheng Ping—can lay claim to a remarkable trajectory in pursuit of what rightfully expects to be perfection in her art, a completeness or wholeness that goes beyond colour and content. It’s an inner thing, you see, which is neither necessary for you, the viewer, fully to understand or indeed immediately to have available to you, or at all, any time soon, or ever. Sure, it’d be great if you attained it, but Ping Zheng the artist is neither overkeen nor reluctant to share that inner core, the driver, to use that anodyne word, if you will, of her creative impulses and production.

Ping Zheng began her life as an artist while still a child, around age 13 to be near exact, in northern China’s Shanxi province, but began loosening up the reins of that heritage (perhaps read bondage?) as a student and early practitioner in London. Born in the East Sea port city of Wenzhou, Cangnan county, Ping Zheng learnt to draw and paint before beginning her formal education.

In conversations during that early period in London, Ping Zheng was forthright about what she didn’t miss about her childhood.

The challenges she faced as a girl child were immense, her recollections of experiences littered with inequities not only as an adolescent female but also as an aspiring artist. Going beyond her visual narratives, Ping Zheng has drawn on and articulated some of those searing memories, talked about early impressions that went into creating her art, and cited specific works that point to that interaction between thought and process.

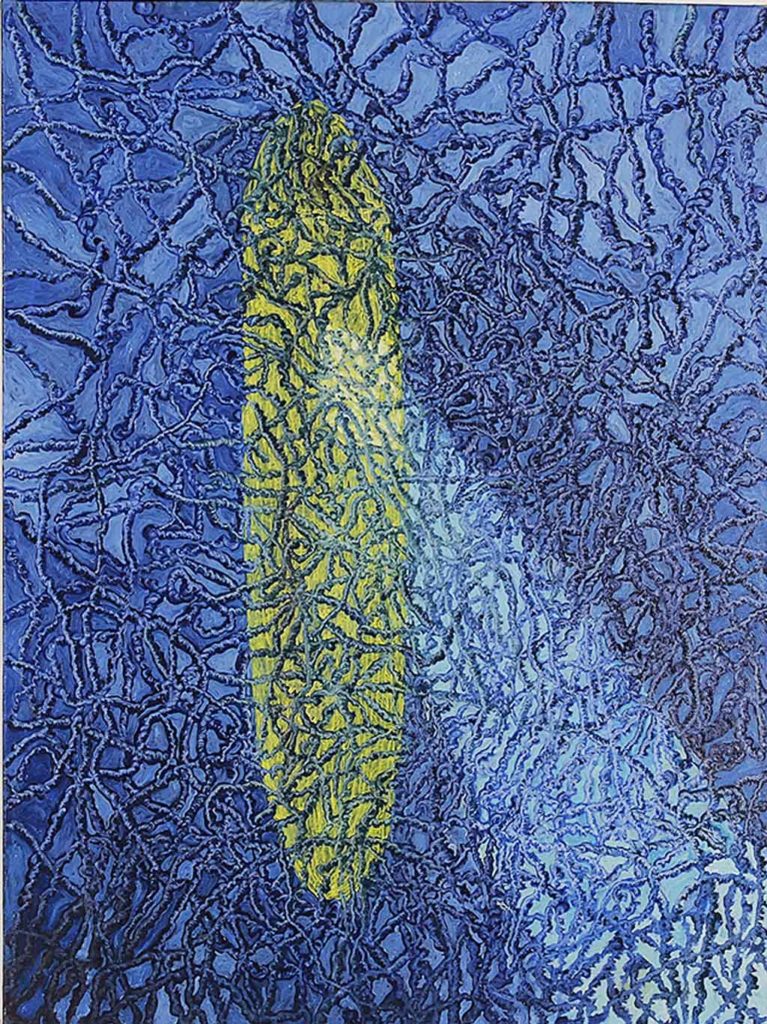

Hints of our inner anatomical selves abound in Ping Zheng’s evolving vocabulary and some of her visual references at least can be designated as icons of a narrative that is distinct, proprietary, singular but also universal. Tentative it isn’t and the expression comes across loud and clear. In that sense, Ping Zheng has arrived at a palette that is liberating both in her choice of colours and form, with perhaps endless possibilities.

Nearly a decade has elapsed since our paths crossed and Ping Zheng’s progression over the period has been steady but slow, neither fully exposed to the viewer’s scrutiny nor identifiable as phases, that word dear to artists, critics and curators alike.

As a foundation student at Camberwell College of Arts, Ping Zheng’s diminutive persona allowed her to ease herself into the shadow of more proactive artist colleagues from China and elsewhere. In retrospect it’s possible to see how that social experience, or rather the lack of some, gave Ping Zheng her precious freedoms to explore and hone her skills.

In the summer of 2016, we communicated on ways of ‘doing something’ about her work and by late summer/early afternoon a structure for a line of enquiry had evolved and, for want of a physical, face-to-face contact, a few alternatives had been agreed upon. What follows is an edited email exchange, part of a larger piece in Eastern Art Report Issue 97:

Sajid Rizvi. What’s your earliest memory of wanting to become an artist?

Ping Zheng. I didn’t dare to think, before I turned 18, that I could want to be an artist, due both to my family matters and the Chinese schools I went to, where art and the teaching of it was very much despised. Another old memory is that I wasn’t welcome in the company of my school mates, even at the kindergarten stage. That meant I had more freedom to paint and draw as my main activity.

However, after I began to study abroad, I found that art was not about how excellent your technical skills were or how good you were in imitating the masterpieces, and I started to understand the meaning of art. I loved art and creating art wherein I could express my own thoughts and feelings.

SR. Once you began creating art, at a tender age, what were your early years in China like?

PZ. I moved from place to place because of my father’s career, but he worked mostly in the northern part of China, which was largely rural and noticeably less in development. My first impression at school was of teachers who were very cruel, physically punishing children with their hands, legs or any other school tools they could lay their hands on. And they didn’t encourage any students to go to art classes. By contrast, when I was in the kindergarten, teachers liked teaching children how to write Chinese calligraphy or paint Chinese paintings with a Chinese brush. I think my kindergarten experience brought me to the first steps of liking and practising art.

SR. You began to be exposed to western art whilst still in China; what were your first impressions?

PZ. When I was 13, my first art teacher in Shanxi introduced me to western Classical Painting, the likes of John Constable, and I loved the beauty of cottages and countryside depicted in my art books.

When I was 16, and by that time in Beijing, I began learning how to paint or draw in the style of Impressionism. But there was a teacher who told me that Pop Art was newer than Impressionism. I was a bit shocked to learn that and wondered what was the latest one could like or learn from in art.

SR. You arrived in London at what is generally regarded as an impressionable age. So, as a young artist, what were your first impressions, especially since you were already introduced to western art while in China?

PZ. My first impression was of so many paintings that I had seen in the art books and were now in front of me in the galleries or museums. They were authentic, the real thing! At college, I couldn’t understand what my school friends were doing about art with all kinds of different materials, and when we had tutorials, many things were completely new to me.

SR. What are the main issues that concern you as an artist? How have those concerns changed or evolved over the years you’ve been living in the West?

PZ. Nowadays I think it is about a country where I want to live. I grew up in a traditional Chinese family with divorced parents, but what was worse was that both of them didn’t like me, due to my being a girl. And my poor, conservative Chinese society wasn’t interested in art education. I found myself fighting with my old memories, with what I was taught and what I was made to believe in wrong ways. Living in the West has given me so much courage and faith.

SR. Do you identify any particular influences, whether individual artists, movements or trends, in your work?

PZ. I am inspired by what I experience in life, the artists and writers I meet. They awaken my history and allow me to face my past. It is also the time I experience in the midst of wonders of nature. They’ve now become my long-term friends. I think I am an autobiographical artist.

SR. After your stay in Europe, what’s your experience as an artist in the United States?

PZ. I now realise that I can invent or create my art language with my paint, forms and colours. I think there is much more to explore and cultivate as I continue to paint. It’s from my imagination, my mix of emotions of the past and present in my memory.

SR. What do you see as your future direction as an artist?

PZ. It’s the very uncertainty of life, being an artist. But it’s also how I have come this far. I know I want to be a good creator which means I need always to work hard. ©Eastern Art Report

Additional notes, Ping Zheng features in a two-woman commercial show, alongside Drea Cofield, 29 June-29 July 2017, at Nancy Margolis Gallery, New York. In a new artist statement 10 July 2017, posted on the gallery’s website, Ping Zheng said (unedited text), “The pieces featured here are, on the one hand, inner landscapes from my memories of the past and present that are virginally created. The places are pure and full of magic, where I could breathe and feel comfortable. Feelings of unease come from my parents’ preference for a son. Growing up, I experienced so many rules being a girl.

“My parents disliked me very much and thought the female body was dirty. In contrast to my brother, the male body was superior. I dream of a world where male and female doesn’t matter. While my paintings look like one thing, they mean another. The viewer can’t identify exactly what is in my paintings, but they are alive and exist in the universe. They form a part of the sky, day and night, mountains or lands, Overall, the artwork straddles the line between figuration and abstraction. They are about my autobiography and take inspiration from relationships in my personal life.–Ping Zheng.”

Also of interest

O Zhang: A talented artist’s trenchant feminism