There’s very little time left to view an extraordinary display of works not usually associated with South Asian miniaturist Abdul Rahman Chughtai at London’s Grosvenor gallery (29 October – 30 November 2014).

A native of British India, born around 1897, Chughtai is cherished by both Pakistan and India, perhaps more in Pakistan because he died there in 1975 after years spent on both sides of the divide that materialised with the partition of the Raj territory in 1947. And he’s not without memories in the wider reaches of British art history either, having lived and practiced in London during the 1930s.

Either through market dynamics or because of their colourful visual appeal, watercolour miniatures on paper in the romantic styles favoured by the courtly ateliers of Mughal emperors and princely underlings of both Hindu and Muslim persuasion are readily associated with Chughtai. This association has tended to brand him, in a modern sense, as a miniaturist. Etchings such as those in this temporary selling exhibition are a rare sight. But decades after his death the full breadth of Chughtai’s work remains unexplored. As an example, not many among millions familiar with his work through popular copies, calendars or posters would know of his expertly executed etchings — refined, sophisticated and physical testimonies to his drive for technical perfection. But here they are, 16 of them, on two floors of the gallery.

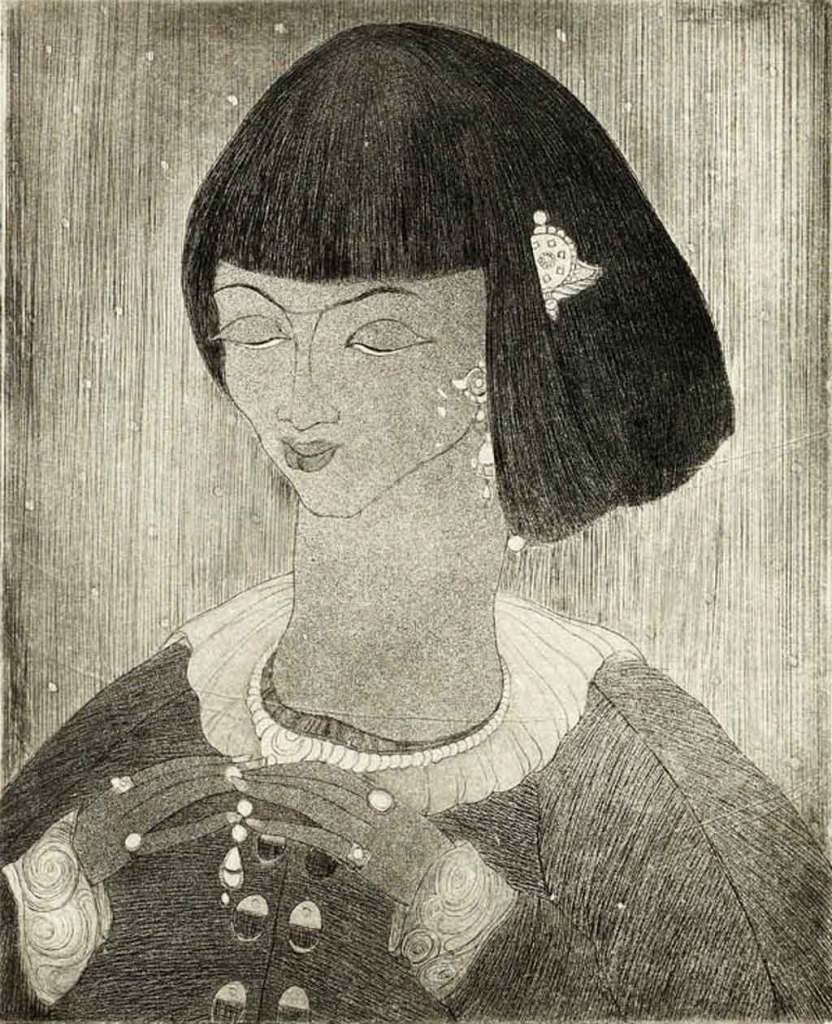

Etching is a time-consuming process requiring patience and skill in equal measures. Chughtai’s etchings aren’t faithful renditions of Mughal lore or memories from a family traceable to the Tatars and Uzbeks of Central Asia and the Caucasus. Exploration, experimentation and reconfiguration abound in most of the works. Amidst reinterpretations of familiar topics imbued with contemporaneity — the stuff of Mughal or Indian folklore — are also explorations possibly informed by exposure to foreign literature and travel. This is noticeable in Chinese Girl, in which the subject’s long neck and large almond eyes contrast with the work’s fanciful title. ‘Chinese girl’ it ain’t, but should that matter? Chughtai’s Chinese Girl is whimsically stylised, perhaps even more so than Vladimir Tretchikoff’s Chinese Girl, which created a stir when it went for a record price at Bonhams London in 2013. In the context of Chughtai’s work, exposure to Chinese and Japanese art in east India through his peers at the Mayo College, Lahore, and his interest in a resurgence in the Bengal School of painting during the period may also have played a part in formulating ideas behind such works.

Nude with Feather, redolent of both persianised Mughal painting and various Indian Hindu schools of painterly styles, references Chughtai’s fascination with the female form without perhaps prolonged exposure to opportunities for observation. The exceptionally pert breasts, fleshy projectiles balanced on a plump figure perched on a hilltop, are right out of Ajanta’s rock-hewn erotica. This was a period when artists, while receiving European and East Asian influences almost simultaneously, tended to paint nudes with distinctive native Indian (usually Hindu) attributes and idealised (invariably Muslim) maidens with princely attire and birds or feathers associated with love and romance.

Other works that feature women with Krishnaesque curled-lip languor packed with sensuality, including Mughal Lady and Mughal Princess, also point to the fusion of styles, tastes and techniques that was afoot from early to the middle of the 20th century and signalled a departure from the elongated persianised beauties of the earlier works. That fusion, call it assimilation of diverse cultural trends in India’s melting pot, found expression in Muslim artists interpreting Hindu subjects, a tradition pursued (in India, not Pakistan) through this century by M F Husain right up to his magisterial but sadly incomplete ‘Mother India’ series, seen 28 May – 27 July 2014 at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Away from the portraiture and women, Chughtai demonstrates his skill and artistic range in etchings that focus on part-imagined and part-documented representations of the common downtrodden in a country in flux before or around Britain’s exit. The etchings have yet to be dated. Most of the characters depicted in varying miserly states of underemployment are evidently of Muslim appearance, with inevitable references to be found in Persian/Urdu poetry of melancholy, hardship and dispossession and much of it romanticised as yet more manifestations of God’s will. The Carpet Seller, in an impoverished northerly setting, evidently Kashmir or thereabouts, exquisitely dates the work with the insertion of a contrasting European figure plucked right out of the Raj.

Chughtai’s Etchings: Editions of a Master. 29 October – 30 November 2014. Grosvenor Gallery, 21 Ryder Street, London SW1Y6PX.

Follow Eastern Art Report on Twitter | Follow the Editor on Twitter