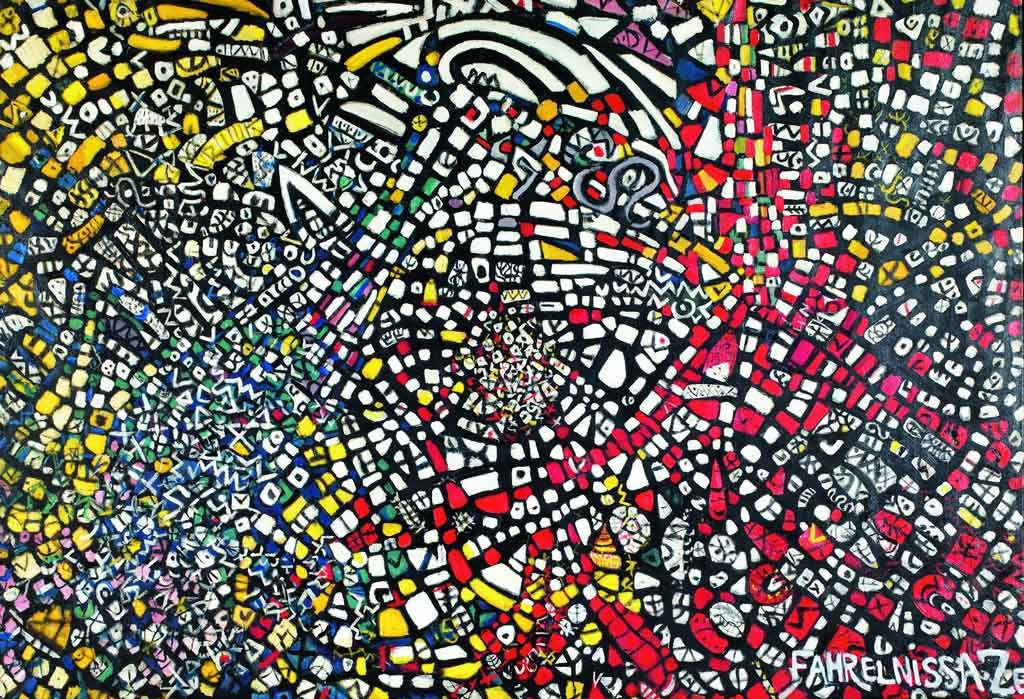

Fahrelnissa Zeid 1953: Triton Octopus. Oil on canvas, 181 x 270 cm. Istanbul Modern Collection/Eczacibaşi Group Donation © Raad bin Zeid Collection. Image: Tate Modern

Come this June (2017), Tate Modern celebrates the life and works of Fahrelnissa Zeid, an artist who can rightly be seen as one of the female pioneers, in the wider Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, of both modernism and abstraction in a western sense, responsive to western aesthetics and sensibilities.

Abstraction, through reinterpretation of Arabic/Farsi/Osmanli/Urdu calligraphic forms, isn’t new to a region that, in Asia alone, stretches from Afghanistan, post-Mughal South Asia and Iran to the Arabian peninsula and the Levant. The wider MENA region, which skirts the Atlantic through cultural cross-fertilisation right up to Mauritania and further south in an area with present-day Mali at its centre, is receptive to this even as it has its own channels to Europe.

The modernism that Fahrelnissa Zeid embraced is rooted, however, in an ongoing phenomenon which is one part dialogue and another part dichotomy. This of course is the westward reach of a region in flux and turmoil, empires in decline through 19th and 20th centuries, the hybrid fruits of western colonialism and eastern cultural and military forays into mainland Europe. It is also a perennial quest and yearning of a people which lives in thrall to creativity, dynamism and above all freedom of expression in Europe.

A native of post-Ottoman and pre-republic proto-Atatürkist Istanbul, Zeid was the product of an era when the cultural boundaries between contiguous nation states emerging from the First World War fused and flourished.

What the Tate calls the first retrospective of Fahrelnissa Zeid may come as a surprise to those of its patrons who may never have heard of her, let alone considered her work in an international context. Now they are invited to reappraise her work in the selfsame framework. But that’s what Tate does. Validation by virtue of display is a kind of anointing that is both privileging and appropriation, in this case a benign and benedictory embrace of the artist in a milieu many MENA artists young and old expressly aspire to. The fact that Zeid’s merit has already been acknowledged in the marketplace over the years, with one sale at Bonhams London realising more than two million pounds sterling, reinforces that elevation of status. Zeid’s scroll-like Towards A Sky, 593 x 201cm, also sold recently at a healthy price, GBP 992,750.

Zeida was born in Istanbul in 1901 in the twilight of the Ottoman empire, a decade before a war of independence that set in motion events giving birth eventually to the Turkish Republic, recently put on course to fateful transformation by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Istanbul—Constantinople to many even to this day—provided Fahrelnissa Zeid with the perfect setting for unbridled innovation. A whole gamut of architectural, artistic and cultural vestiges of the Ottoman metropolis and fading empire proved to be a playground for Zeid’s fertile imagination.

Privileged as undoubtedly she was as a member of the Ottoman elite who later married into the Hashemite royal household, Zeid was able to draw on an environment redolent of Istanbul’s myriad pasts she breathed in, combining Islamic and Persian influences with Byzantine symbolism that outlasted the regime change.

Fahrelnissa Zeid surprised early viewers with both size and subject matter of her work. Canvases as wide as five metres were unheard of then, except to the discerning few who had been to Europe or seen European tapestries for comparison. Contrasts with figurative content and technique of Ottoman and Persian miniature painting were also received by some as novel or naïve or tolerated as another strain of experimental work that marked early avant-garde in a rapidly evolving modern Turkey. Alongside painting Zeid drew and devised three-dimensional work that expanded her oeuvre but also opened up possibilities for other artists in that evolving scene.

Events in Turkey and its environs determined Zeid’s life and work was not to remain bolted down to a downgraded capital city which, with the rise of the republic, found itself overshadowed by the new capital, Ankara. This and the family’s reversal of fortunes, not least the destruction of the Hashemite royal extension in Iraq (and eventual rise of Saddam Hussein decades later), forced a move to Europe that proved fortuitous. Exhibitions in London, Paris and elsewhere followed, earning praise and wider recognition.

Zeid spent the last years of her life in Amman, Jordan, where she transformed her home into an informal art school and surrounded herself with a cosmopolitan group of female students. Alongside Zeid’s activities the Jordanian capital over the years vied, as it were, with Baghdad as a magnet for artists from near and far. Amman was one of the first cities to found a contemporary art gallery/museum, thanks to the efforts of another member of the royal household, Wijdan Ali, an artist and curator in her own right and more recently a founder of Jordan’s first art and design faculty at the University of Jordan. Fahrelnissa Zeid died in Amman in 1991, aged 89.

The exhibition at Tate Modern (13 June – 8 October 2017) will travel to Deutsche Bank KunstHalle in Berlin in November 2017. © Sajid Rizvi.

Additional Notes: Sponsored by Deutsche Bank, this welcome retrospective of Fahrelnissa Zeid reappraises her work in an international context as Tate repositions itself. The event coincides with a growing realisation in the West that a greater exploration of multiple, simultaneous or independent modernisms is essential and timely.

The Zeid exhibition brings together her paintings as well as drawings and little known sculptures, made over four decades and in different locations, including London, Paris and North America. Tate mirrors an increasingly revised view that the international story of abstract art, to mention one genre under review here, will remain incomplete without a more open-ended enquiry of other cultural systems and artistic practices within that existed outside the European or western spheres.

As Tate rightly points out, Zeid was one of the first women to receive formal training as an artist in Istanbul, continuing her studies in Paris in the late 1920s. But there were women active in the arts, not just of letters but of pencil, pen, paint and brush in cloistered or protected surroundings in Iran and Iraq, central and inner Asia, South and Southeast Asia as well as Arab and Persian communities in East Africa and the Indian Ocean region. Many were unschooled in a modern sense but some underwent apprenticeship from humble or anonymous masters.

In 2013 Tate highlighted the life and works of Lebanese modernist Saloua Raouda Choucair but the achievements of Iraqi and Iranian women artists from the 19th century onwards remain to be recognised on a wider level. On balance, in terms of audience growth and wider recognition, Arab and Iranian women artists have fared better in North America than in Europe. A few correctives at the Tate and elsewhere, therefore, should be mutually rewarding. Sajid Rizvi